Last Updated on 1 month by Publishing Team

What is Lymphatic Filariasis?

Lymphatic filariasis (commonly known as elephantiasis) is a parasitic disease caused by microscopic, thread-like worms. The adult worms only live in the human lymph system. The lymph system maintains the body’s fluid balance and fights infections. Infection is usually acquired in childhood causing hidden damage to the lymphatic system.

Lymphatic filariasis affects over 120 million people in 73 countries throughout the tropics and sub-tropics of Asia, Africa, the Western Pacific, and parts of the Caribbean and South America.

Lymphatic filariasis can be a danger in Fiji due to the tropical climate and wet season that gives rise to many mosquito-borne diseases. However, cases are fairly rare due to the Ministry of Health’s mass administration of preventative medicines in Fiji over the last decade.

How is lymphatic filariasis spread?

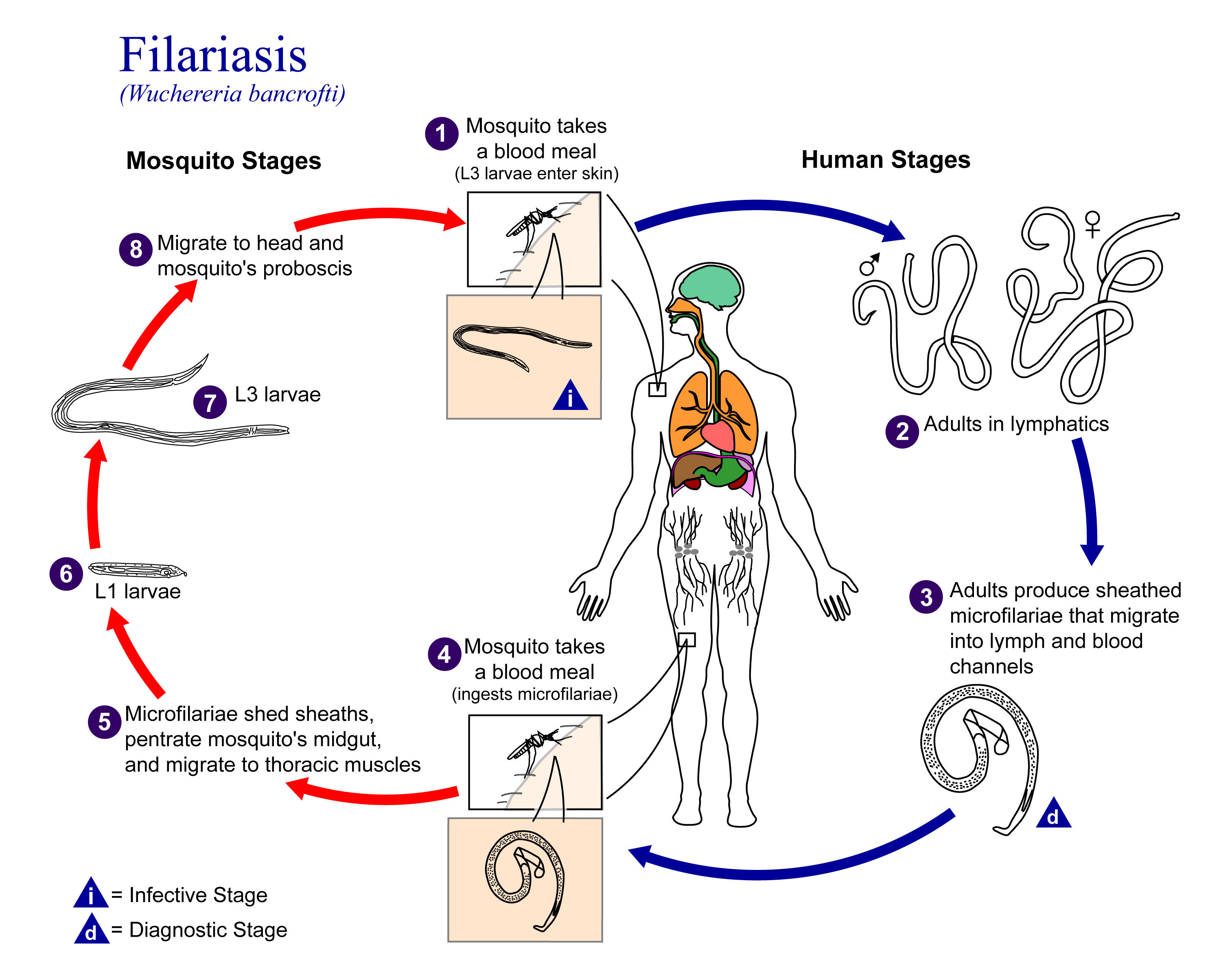

The disease spreads from person to person by mosquito bites. When a mosquito bites a person who has lymphatic filariasis, microscopic worms circulating in the person’s blood enter and infect the mosquito. People get lymphatic filariasis from the bite of an infected mosquito.

The microscopic worms pass from the mosquito through the skin, and travel to the lymph vessels. In the lymph vessels they grow into adults. An adult worm lives for about 5–7 years. The adult worms mate and release millions of microscopic worms, called microfilariae, into the blood. People with the worms in their blood can give the infection to others through mosquito bites.

The Life Cycle of Filariasis Source: Wikipedia.org

Who is at risk for infection?

Repeated mosquito bites over several months to years are needed to get lymphatic filariasis. People living for a long time in tropical or sub-tropical areas (like Fiji) where the disease is common are at the greatest risk for infection. Short-term tourists have a very low risk. An infection will show up on a blood test.

Signs & Symptoms Of Lymphatic Filariasis?

Lymphatic filariasis infection involves asymptomatic, acute, and chronic conditions. The majority of infections are asymptomatic, showing no external signs of infection. These asymptomatic infections still cause damage to the lymphatic system and the kidneys as well as alter the body’s immune system.

Acute episodes of local inflammation involving skin, lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels often accompany the chronic lymphoedema or elephantiasis. Some of these episodes are caused by the body’s immune response to the parasite. However most are the result of bacterial skin infection where normal defences have been partially lost due to underlying lymphatic damage.

When lymphatic filariasis develops into chronic conditions, it leads to lymphoedema (tissue swelling) or elephantiasis (skin/tissue thickening) of limbs and hydrocele (scrotal swelling). Involvement of breasts and genital organs is common. Such body deformities lead to social stigma, as well as financial hardship from loss of income and increased medical expenses. The socioeconomic burdens of isolation and poverty are immense.

Above: A woman suffering from LF displays classic symptoms of the disease: swelling of her leg due to fluid build-up caused by blockage of her lymph system by worms.

Source: Andrea Peterson (www.neglecteddiseases.gov)

How Is Lymphatic Filariasis Diagnosed?

The standard method for diagnosing active infection is the identification of microfilariae by microscopic examination. This is not always feasible because in most parts of the world, microfilariae are nocturnally periodic, which means that they only circulate in the blood at night. For this reason, the blood collection has to be done at night to coincide with the appearance of the microfilariae.

Serologic techniques provide an alternative to microscopic detection of microfilariae for the diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis. Because lymphedema may develop many years after infection, lab tests are often negative with these patients.

How can I Prevent Infection?

Avoiding mosquito bites is the best form of prevention. The mosquitoes that carry the microscopic worms usually bite between the hours of dusk and dawn. Living in Fiji, there are many good reasons to avoid mosquito bites, such as other serious diseases as Dengue Fever. You should protect yourself by;

- Stay indoors

- Wear insect repellent when outdoors

- Use mosquito nets when sleeping

- Install fly wire on your windows and doors

- Wear long sleeves and trousers if working outdoors for long periods

You should also take the time to destroy mosquito breeding habitats in your home and community by following these steps, especially in the lead up to and during the summer wet season;

- Clear leaves and other rubbish from roof gutters and from around the house

- Remove old tyres

- Don’t leave empty tins, bottle, buckets or drums around, turn upside down to prevent stagnant water forming

- Cover stored water drums securely

- Cut long grass

- Work with your village or neighbourhood to remove common breeding habitats from shared areas

- Remove potential indoor breeding habitats including vases, water try under fridge, empty bottles and cans, stored water

- Remove coconut shells and husks as they accumulate water for mosquito’s to breed in.

What is the treatment for lymphatic filariasis?

Over the last decade, the Ministry of Health has been involved in the large-scale prevention of lymphatic filariasis which is possible by stopping the spread of the infection,. Large-scale treatment involves a single dose of 2 medicines given annually to an entire at-risk population in the following way: albendazole (400 mg) together with ivermectin (150-200 mcg/kg) or with diethylcarbamazine citrate (DEC) (6 mg/kg).

These preventive chemotherapy medicines have a limited effect on adult parasites but effectively clear microfilariae from the bloodstream and prevent the spread of parasites to mosquitoes. Large-scale treatment conducted annually for 4-6 years, treating all persons living in areas where the infection is present can interrupt the transmission cycle.

The Ministry of Health conducted this program in Fiji backed by WHO’s Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis, which was launched in 2000 and had reached 56 countries by 2012.

By 2012, 56 countries, including Fiji had started or completed implementing large-scale treatment through mass drug administration (MDA). In Fiji, coverage of the MDA reached just over 94% of the population. THE MDA program is ongoing in Fiji.

Recent research data show that the transmission of lymphatic filariasis in at-risk populations has dropped by 43% since the beginning of the GPELF.

You can read more in this report.

Most Information on this page adapted from: